The Red Strings Club perfectly taps into the classic, underdog tales that permeated 80s cyberpunk literature. While the imagery in this game is less gritty than stories like “Johnny Mnemonic” or “El Pepenador,” it takes the same deep philosophical approach about the future of humanity that has always been cyberpunk’s trademark—and what a glorious tale the strings weave in this game. Its heart lies in a tech-nior storyline, but its soul makes us question how far we’re willing to expand technology to create a psychotropic utopia, even when that fictional world has already expanded to include cybernetic and biomatter implants.

Smattered with metacognitive moments—the game is very aware of itself—The Red Strings Club is set in a bar by the same name. Players control three separate characters: Donovan, the implant-free guru bartender and information dealer who crafts cocktails based on his patron’s emotions; Brandeis, both Donovan’s boyfriend and partner in crime, heavy implant user and freewheeling rebel agent; and Arkasa-184, a highly sophisticated android that randomly stumbles into the bar, broken and nearly in pieces. Players will interact with a variety of characters who are also heavy implant users, afraid and crippled by their own perceived flaws, and just so happen to work for the mega corporation, Supercontinent Ltd., that designed and manufactured their implants. The information provided by each of these characters is crucial to uncovering the motivation behind Supercontinent’s latest program, Social Psyche Welfare, and figuring out how to sabotage it.

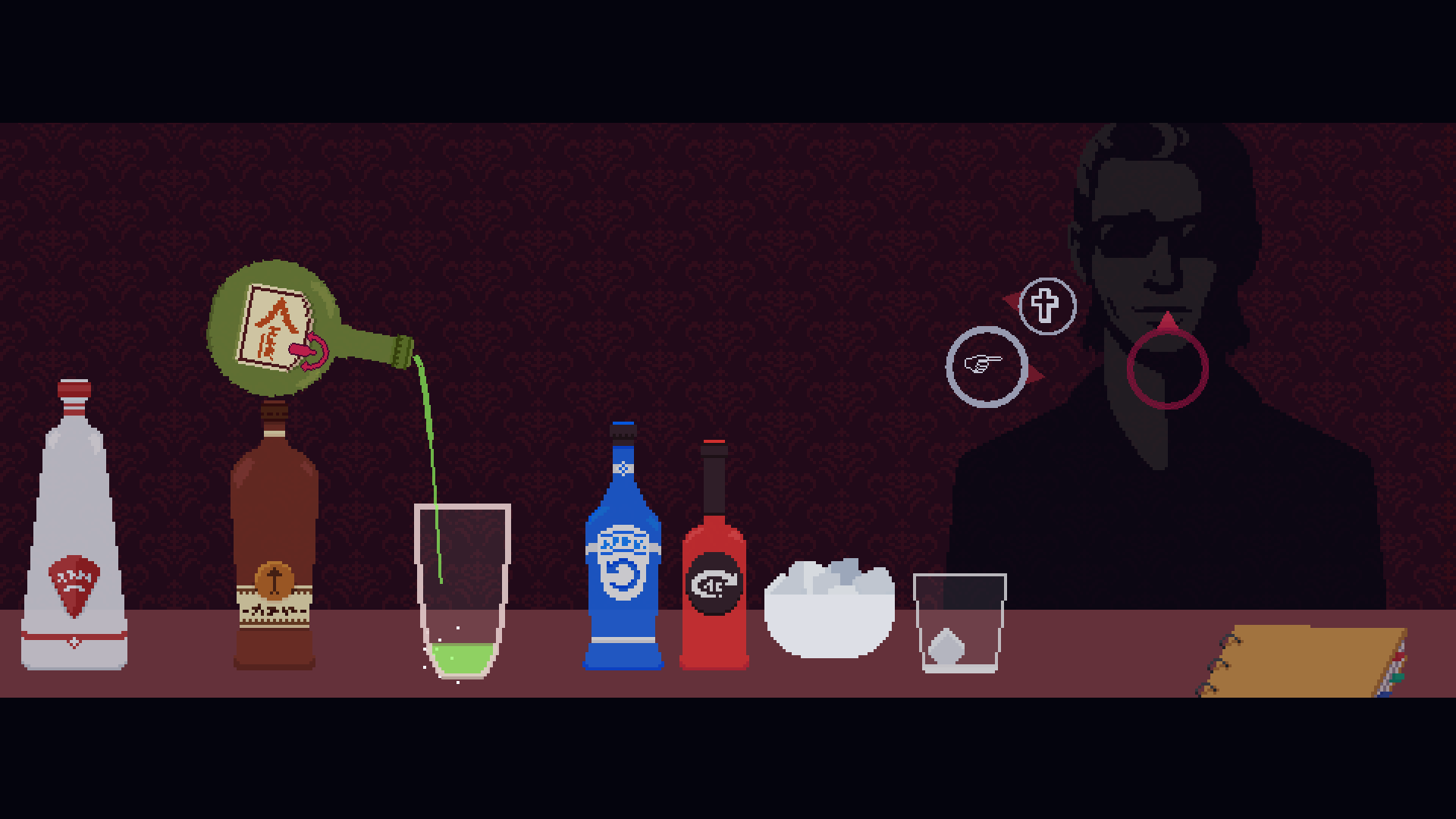

Players will spend most of their time collecting information about the mega-corp’s plan from behind the bar as Donovan. Playing the muse, the goal here is to tap into the right emotions of the patrons to fulfill information objectives. It’s a simple system; each liquor moves the circle over a projection of the patron’s soul right or left, up or down. Ice cubes placed in the tumbler shrinks the circle for the more refined or buried emotions. For harder to reach emotions, there’s a shaker to blend two liquors together to the circle diagonally. This system was easy to pick up, and it was fun mixing drinks for other people since there was an underlying strategy. After a sometimes pleasant but always interesting conversations, Arkasa collects and synthesizes information from the patrons based on their personalities and how they interact with Donovan, and then quizzes him after each one leaves. Guess seven out of ten correctly and win a prize. Score a D or F, and nothing special happens. No do-overs either, except on the first one.

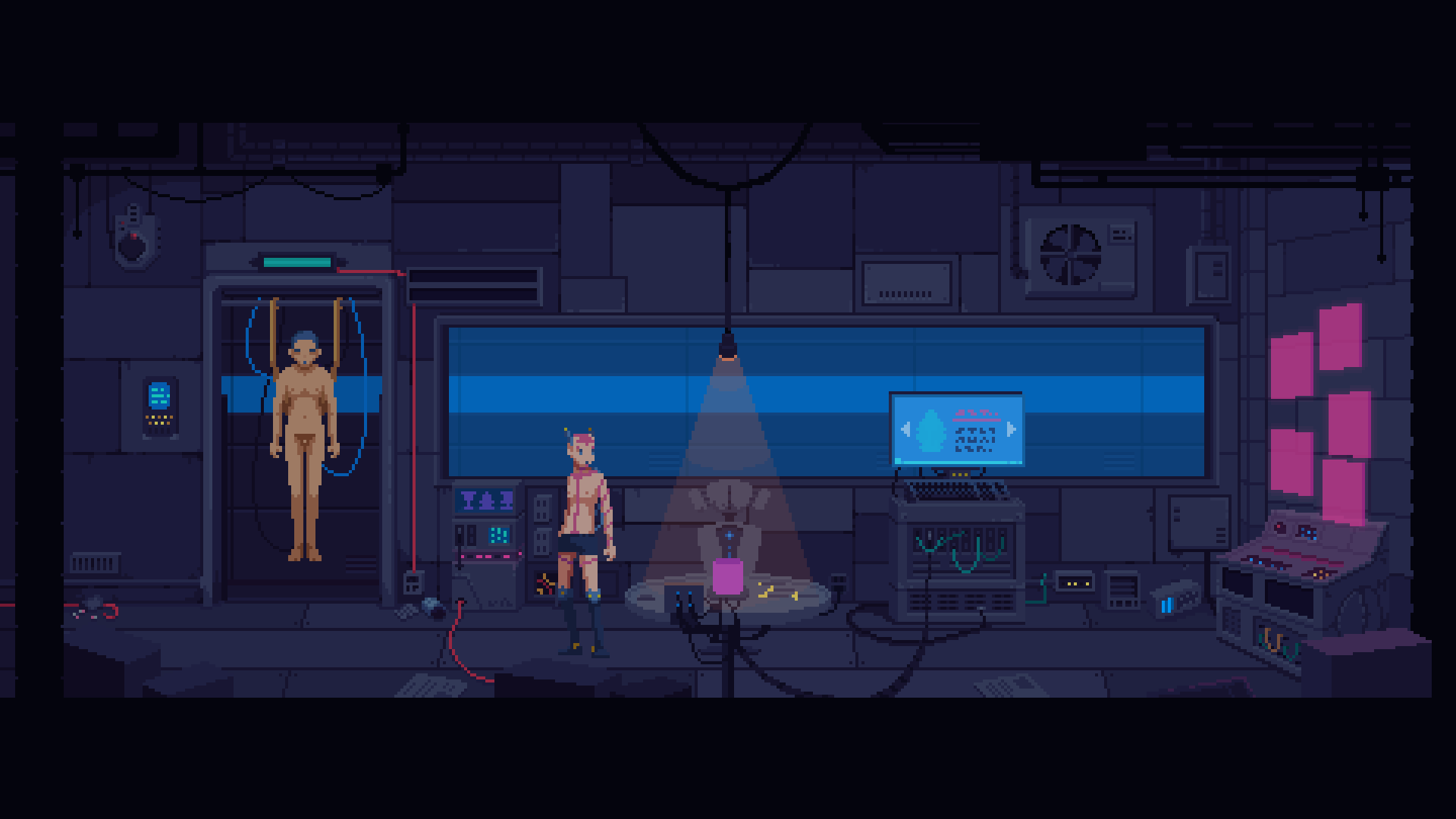

The second playable character is Arkasa, after Brandeis mindhacks the android’s memories. Without saying too much, Arkasa comes to play a large part in the story, but not before we find out where they came from. This part introduces players to the second non-dialogue mechanic in the game: pottery. Arkasa works in a lab of sorts, throwing biomatter like clay on a pottery wheel to shape into emotion or personality altering implants for customers—who roll into the scene assembly line-style, naked, and hanging from their shoulders. Here the player chooses from a selection of implants to mold into a specific shape, pop into the customer, and send them on their way. Each customer has a different social problem, and it’s up to Arkasa to make them happy.

This part of The Read Strings Club is an odd juxtaposition of technology and art. This activity itself is okay, but the real fun of this scene is in choosing the implants for each client—and may have consequences later in the game. One client, for example, wants to become a famous cosplayer. There are different implants that players can install to help make this possible: increase charisma, be unaffected by social norms, etc. The writing in this scene is so strong that the pottery mechanic isn’t really needed, but I have a soft spot in my heart for it only because it reminds me of high school ceramics and how my teacher pushed his students to create better work by calling it C.R.A.P., meaning Ceramics Requiring Additional Practice.

Brandeis is the final playable character. Aside from one scene, his role in the story is high-stakes. He’s the one that gets into perilous negations and breaks into places he doesn’t belong. How players control him isn’t as mechanically complicated as bartending or throwing biomatter, but his actions are central to the climax of the story. He’s the hacker. He’s the voice manipulator. He’s the one that does all the dangerous stuff, putting his life on the line. And that’s just the way he likes it. The final scene with Brandeis tests the player’s observation and conversation skills they’ve been honing up until the end of the game. It’s not enough to simply know who to call to get the right information; players will need to be a sharp study of the relationships between the other characters, even though they interact with them one at a time.

With all that said, however, The Red Strings Club’s superpower is not in the mini games or mechanics, or even the plot itself. The concept of Social Psyche Welfare is as fascinating as it is terrifying, and the trope of stopping an evil corporation from doing evil things has been done time and time again, but the characters and the dialogue are what make this game something special in terms of the overall storytelling. Each character has their own voice. By that I mean if you were look at their dialogue on a piece of paper without their name attached, you’d be able to tell who is speaking. This is what good writing looks like. Interacting with each character felt like I was interacting with a real person. The characters are so well-rounded and effortlessly allow the player to create an emotional connection to every one of them. I wish the game was longer so I could spend more time with these characters.

The Red Strings Club uses every cybyerpunk trope—implants, sentient androids, all powerful corporations—in ways that are meaningful. Instead of sending players on a high-tech, gun blazing mission with lots of unnecessary violence, all the detective work is done with cunningness and charm. The characters are incredibly memorable. The ending is something only a game could achieve, confronting players unexpectedly in real-time with hard questions about their views on society and technology, morality and free will. If your playthrough is anything like mine, you’ll take extended periods of time answering Arkasa-184’s philosophical questions. And it’s as well you should, since your answers will directly impact the future society of this game.

For more information on The Red Strings Club, check out Deconstructeam’s website. A copy of the game was provided by the publisher.