According to author and professor Roger Rosenblatt, writing is not worth much “unless it moves the human heart.” As far as I am concerned, that standard should apply to all forms of art, and video games, my friends, are an art form. In my experience, few games have illustrated the ability to inspire emotion more profoundly than The Last of Us. While weaving a soul tearing narrative and painting fascinating, tortured characters, The Last of Us changed my standard for video game storytelling in its opening scenes.

Now, before anything else, there’s something that you should know: I was that kid that cried at the end of Ocarina of Time.

Yup.

Just wanted to get that out in the open before anything else.

See, seven-year-old me was even then trying to find meaning in and an emotional connection with video games. For some games, it was difficult or impossible. Let’s be honest, Super Smash Bros isn’t exactly a character-driven saga that pries at the depths of human feeling. Yet other games led me to ascribing emotions and meaning to even the blandest and most expressionless characters.

I mean, Ocarina of Time? Yeah, maybe you could feel for Zelda resigning herself to near solitude in a broken and barren kingdom after Ganondorf’s rule, or maybe your heart could ache for all of those left to suffer, or even for how Link was not given a choice in whether he would stay in the present or return to the past. However, seven-year-old me did not cry for those things. Heck, seven-year-old me probably only registered those issues on a subconscious level, if that. No, he cried because he was convinced that Link and Zelda were in love and should not have to separate.

In other words, I was romantic AND naive.

I wanted to see emotional meaning in Link’s actions when, frankly, we don’t know diddly-squat about him as a person. Yes, there is an argument to be made for a blank-slate character and projecting our own imaginations or personalities upon him, but that seems like a bit too much to shed tears over.

Even so, there was SOMETHING to the game. There was a story and that snared my imagination. Mario Kart 64 and the like were fun, but I was always drawn back to the games with a plot. If there were cutscenes or anything from which I could learn about the characters, I lapped it up. I would even get rather *ahem* vocally annoyed with my friends for skipping the cutscenes in Halo. Again, Halo is not exactly Oscar-winning material, but it was never enough to just go down a hall and shoot things. I had to know why.

Now whenever someone suggests a new game, I always ask one question: Does it have a good story?

With rare exceptions, I cannot feel invested in a game unless there is something more at stake than a “Game Over” screen. Perhaps I seek games that evoke feeling because I am an avid reader and stories make my world go ‘round. It could be because I think that art should evoke emotion or at least make you think and reflect. Or it could just be to fill that voracious inner void that is the meaninglessness of human existence. You get the idea.

One game to hit that sweet spot and fill that deep, dark, masochistic hole in my soul was The Last of Us. Specifically, those first fifteen minutes of gameplay drove such an indelible brand onto my mind that it seems impossible to talk about video games evoking feeling without at least mentioning it.

Warning: Spoilers ahead for The Last of Us

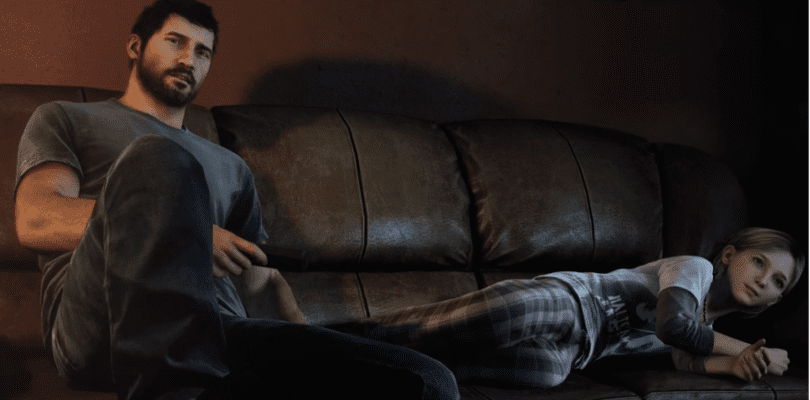

From blackness and silence appears a tomboyish blonde girl who has fallen asleep on a ratty, well-loved sofa. A door opens and we hear a man talking on the phone, softly arguing with someone on the other end about work. Frustrated, yet trying not to wake the sleeping girl, the man determines that the conversation can wait until morning and hangs up. Despite his efforts, the girl stirs.

“Fun day at work, huh?” she observes through bleary eyes as she makes room for him.

“What’re you doin’ up?” the man asks, “it’s late.”

Turns out, she was waiting to give him his birthday present, since she probably has not seen him all day. The wristwatch she gifts is beautiful and masculine, seeming to perfectly fit her rugged, weary father, and it is well beyond her means.

“Where did you get the money for this?” he asks after digging her with a typical dad joke.

She snorts. “Drugs. I sell hardcore drugs.”

“Oh good,” he replies, picking up the remote and flipping the TV on. “You can start helping out with the mortgage then.”

“Pfsht. Yeah. You wish.”

Next thing we see, she is once again asleep on the couch. Her dad carefully carries her to her bed, tucks a stray hair back, and whispers “Good night, baby girl” before he turns off the light.

That by itself is an experience that so many of us have shared: Falling asleep waiting for our parents to come home or getting caught on the couch when we should be in bed. Exchanging bad jokes, drifting off next to them with the TV on, and being lifted and cradled to our beds. . . Even if that is something that we have not been so lucky to have in our lives, it is something that we can imagine and empathize with. It is something loving and beautiful and real.

Taking control, we step into the girl’s shoes as she wakes to an alarming call from her uncle. Glancing around her room, we see posters, diaries, pictures. . . all sorts of accouterment that tells us who she is. The panic and terror that hangs on the periphery of the scene grows closer as a distant explosion rattles the windows and police cruisers blaze past, sirens blaring. She looks for her dad, calling for him, doing her best to stay collected when alone and uncertain. When he reappears, he is spattered in blood and breathing hard, his voice strained as he tries to sound calm for his daughter’s sake. Moments later, though, their neighbor smashes through the door and charges them before the dad is forced to plant a bullet in his throat as his daughter watches.

Even as she processes the shock, she is ushered into a jeep that her uncle pulls up to the house. She watches as they pass stranded families on the street, sees their neighbor’s barn illuminate the night with flames, and witnesses people tear each other apart with their fingernails and teeth.

While fleeing the madness, they crash the car, breaking the girl’s leg, and we begin to play as her father. Carrying his daughter – our daughter – through crowded streets filled with rushing, screaming people and lit by ignited gas stations and cars, this Texas suburb now resembles a Mardi Gras pulled from Dante’s Inferno.

While fleeing the madness, they crash the car, breaking the girl’s leg, and we begin to play as her father. Carrying his daughter – our daughter – through crowded streets filled with rushing, screaming people and lit by ignited gas stations and cars, this Texas suburb now resembles a Mardi Gras pulled from Dante’s Inferno.

They flee, the father running as best he can, the wheezing snarls of the infected mere feet behind, when salvation arrives. A blinding light flashes over them and gunshots punctuate the scene as two maddened people are put down with a precise shot each from a soldier. Looking into that soldier’s glaring flashlight, however, soon changes our sense of relief to dread as our savior levels that light at us. The white light we sought to keep us safe erupts with bullets, knocking us back to tumble down the slope. Before the soldier can complete his objective, though, our brother – our uncle – sneaks up and drives a bullet through his skull. The gun and the body drop away and, just as we allow ourselves relief, we see the girl.

Gasping, hiccuping, she shudders and struggles to breathe between tears and shock. She, who is also “we,” whimpers as her dad pulls her into his arms, pressing down on the bullet wound in her – our – stomach left by the deceased soldier. We, the father, whisper kindness and encouragement, trying not to panic.

“I’m going to pick you up now,” he says as he pulls her up and she squeals in agony. We glance, frantic, at our brother – our uncle – silently pleading for help or an idea of what to do.

We look back and the girl’s eyes that were tight with fear and pain are now wide.

Blank.

Staring, but not seeing her dad.

And we cry.

We beg for God not to do this, for her not to do this, not to leave. We hold the body, the small, fragile form that was our daughter, and rock it, as if we can lull her to sleep or comfort her as she wakes from a nightmare. But the girl is no longer there. Our daughter is gone.

It is only the flash to black and the game’s title in stark white letters that bring us back to ourselves. Only then do we remember that this has been a “game,” that we were “playing” this and propelling these characters through this horror of our own will.

Sitting back in my chair at the time, I wanted a moment to consider that, to think, to digest, to cope with that loss. Never have I had a child, but The Last of Us made it so real; made the love between a smart aleck daughter and a struggling father so real, that their separation made me want to bleed for her instead, just to hope that she would make it through.

That moment has haunted me ever since.

There have been others, and The Last of Us by itself was chock-full of poignant encounters, but that one scene flits through my mind too often to be put aside. That scene, and the feelings that it evoked, have become my golden standard for video game stories ever since. Heck, it even made me start taking zombie stories seriously. Before that, they had seemed too dumb to merit attention. If a game can make me feel even half as invested as The Last of Us did in those first fifteen minutes, then it is something worth seeing through. If a game inspires that kind of emotion, then it justifies my belief that games can be beautiful and powerful storytelling mediums.

Now I anxiously wait for the next game to make me feel so that I can rave about it to anyone who will listen.

What were some of your most emotional gaming moments? Share them with us in the comments below or on social media.

More information about The Last of Us and the highly anticipated sequel can be found on the official website.